Test Driven Development

TDD can be hard and feels like doubling your code, but the benefits far outweigh the extra work.

Written by: Alex Root-Roatch | Thursday, May 23, 2024

The Three Laws of Test Driven Development

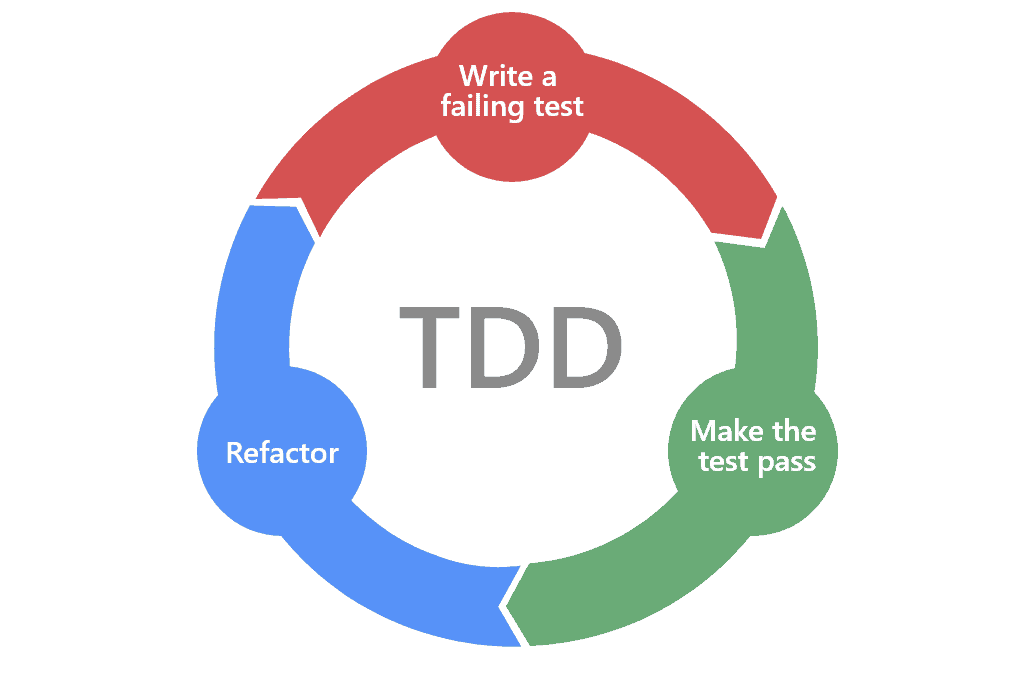

Test Driven Development (TDD) is a method in which the tests for your code are written before the code itself. It is a repetitive cycle of three step:

- Write a failing test.

- Write code to make the test pass.

- Refactor the code if necessary/desired, making sure all the tests still pass.

There are three laws of TDD:

- You may not write production code until you have written a failing unit test.

- You may not write more of a unit test than is sufficient to fail, and not compiling is failing.

- You may not write more production code than is sufficient to pass the currently failing test.

The ending result is a codebase in which every line of code that you've written is tested, and as Uncle Bob taught us, we shouldn't be okay with shipping code that isn't 100% tested. Shipping code when we're not sure if it works properly, according to Uncle Bob, is simply unprofessional conduct.

TDD also makes sure your code is written in a testable (and therefore maintainable) way, prevents you from writing unnecessary code, minimizes debugging time, and eliminates fear that you'll accidentally break something, which empowers you to refactor often and prevent code rot.

Maintainably Written Code

Code that is easily testable is often code that is well-structured and has minimal couplings. After all, trying to write a test for a function that does multiple things, or for modules that have multiple dependencies on one another, is difficult if not impossible. That's why many developers find themselves refactoring their code once they've decided to write unit test.

If you start with the tests, however, your code is easily testable from the start. This also means that your code is written in a way that probably follows best practices like the Single Responsibility Principle and the Open Closed Principle.

Avoid Unnecessary Code

How often have you decided to jump right into writing code in order to figure out what you wanted to write, only to realize you wrote overly complicated code, spent just as much time, if not more, refactoring the code, and deleting half (or more!) of the amount of code you originally wrote? I know I have.

In TDD, however, we start off by breaking the problem down into it's simplest, smallest part, and gradually add features from there. Every line of code we write is directly related to a feature we are implementing rather than being based on some general idea of how we think we should structure the code. The code and its structure are a result of implementing its necessary features.

This may feel like a more difficult way to get started, but thinking of the project in terms of testable chunks actually helps you understand the project better and then only write code that's needed.

The Bowling Game Kata

Let's use the Bowling Game Kata as an example. We can start off by simply saying that if we have zero rolls, our score-game function should return a score of zero. So we create the function and make it return zero. That's it. No math equations yet. Remember, we only write as much code as is needed to make the test pass.

Then we can say that if we roll all ones, we should get a score of 20. Now we can write some math to create that sum.

Now we might move on to thinking about how if we roll a spare, we need to add the value of our next roll to the score of the frame with the spare in it. Ahhh, now we've discovered the need to organize our rolls into frames. At this point we can decide to create a new function to do that.

Once we've made that function and insured it handles all of our use cases, from entering nothing through handling spares and strikes, then we can implement it into our score-game function. At that point, we'll write tests to make sure that strikes and spares are returning the proper total score, and we might be surprised to find that our tests already pass!

And just like that, we're done. Our production code was completed before we even realized it. Of course, we still wrote those final tests to make sure that those use cases were covered.

Fearless Refactor

As Uncle Bob says, the number one reason code rots is because the developers are afraid to make changes to it. In poorly structured code bases, the smallest change might cause a domino effect of breaking the code in a bunch of other places. So instead of owning the code and taking responsibility for it and its bugs, the developers simply don't touch it and thus can't be blamed for the breakages that didn't happen.

But if all of your code is covered by tests, then there's no reason to be afraid of breaking it. The tests will tell you if something broke and tell you where the bug is. TDD advocates and enables refactoring so fervently that it's the third step in the TDD process. As soon as you get those tests to pass, refactor if you can and make sure the tests still pass.

When developers aren't afraid to fix things, they can make a habit our of routinely improving the code every time they touch it. That prevents it from rotting. It's just like straightening up the pantry a little bit every time you put your cereal box away. It keeps things clean and organized rather than falling into a pile of chaos that you wish you could burn down and rebuild.

Goodbye Debuggers

There's no need to practice using debugging tools quickly and efficiently, zooming through code with all those hotkeys to find and fix bugs. If you start by writing tests and then write the code that makes those tests pass, the bugs are detected one at a time as you're writing the code and are immediately fixed before moving on to the next feature/test.

Conclusion

TDD is hard. It forces us to be intentional in the way write our production code. But that discipline is rewarded with the ability to refactor code as we see fit without fear of breaking things, a huge decrease in debugging time, cleaner, more maintainable code, and code that we can be confident shipping because we know every line that we wrote was tested.