Understanding Minimax in Tic-Tac-Toe

The Minimax algorithm is a handy way to calculate the best possible next move in a two player game, but it can be tricky to implement.

Written by: Alex Root-Roatch | Tuesday, June 11, 2024

Introduction to Minimax

The minimax algorithm is a backtracking algorithm for finding the best move in a two player game. It is referred to as a "backtracking" algorithm because it plays through all the possible future moves of both players in order to find all the different possible endings to the game, then rewinds and plays the move with the best chance of winning the game.

In order to do this, it sees one player as the "minimizer" and the other as the "maximizer." At the heart of all of this is an evaluation function that returns a negative number if the minimizer won the game, a positive number if the maximizer won the game, and a zero if it's a tie. Therefore, the minimizer will always pick the outcome with the lowest score, and the maximizer will always choose the outcome with the highest score.

Tic-Tac-Toe

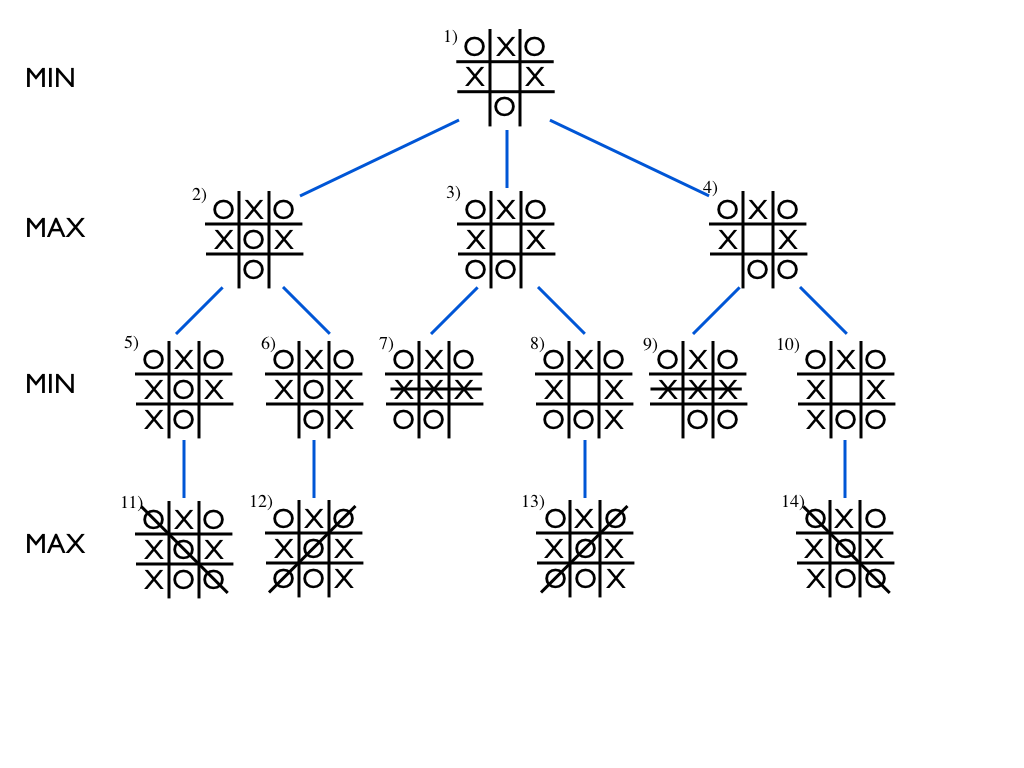

Let's explore this with a tic-tac-toe game tree.

Here we see a board with three possible moves, and it's O's turn. Let's call O the maximizing player.

Before the algorithm runs, it's going to check our board state to see if the game is over, and if so, it's going to return a score like mentioned above. Since we have three possible moves, it will play the first possible move. The next move after that is going to be the minimizing player's turn, which is X in our example, so when we recur, we need to switch players and find the best move for that player. We will keep doing this until we reach a terminal state, which is either X winning, O winning, or a tie.

If we look at board 2 in the image, we see it leads to O winning in both outcomes, board 11 and board 12. So that move gets awarded a score of +10.

Board 3 is a little more interesting. The first move after O plays, X wins the game. Board 7 gets a score of -10. Board 8 leads to an eventual win by O, which is +10. So which score do we give the move in board 3? In minimax, both players are always playing their best next move. Since the minimizer will always choose the lowest of the two score, we know it will choose the move in Board 7. Therefore, Board 3 also gets a score of -10.

For the move in Board 4, we see the same thing happen. So of our three moves:

- The move in Board 2 scores +10

- The move in Board 3 scores -10

- The move in Board 4 scores -10

Since O is the maximizing player, it will always choose the move with the highest score. Therefore, the algorithm reports back that playing the center square is the best course of action, and that's the move the computer player will make.

Depth

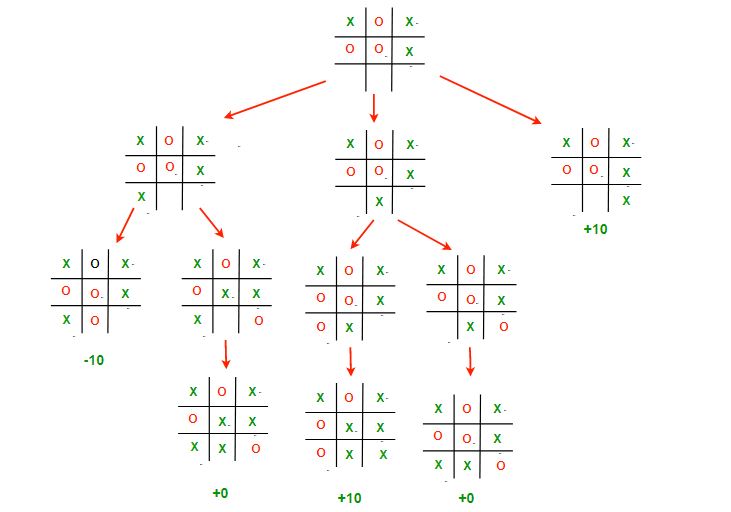

That works, but there is one snag: our algorithm will always pick a path to winning, but it might not choose the quickest path. Consider this example:

X is now the maximizing player. Here we see that X could get three-in-a-row in the right column in three moves, or it could get it in one move. Currently, the second move (playing the bottom middle) will get the same score as the third move (playing the bottom right), so our algorithm might choose the second move when it should choose the third.

We can fix this by adding a depth parameter to our minimax function, which will start at zero and be incremented on each recursive call. That way, the program will have a way of knowing how many moves it took to get to that winning outcome. When minimax reaches a terminal condition, it will subtract the current depth from the score if it was a win for the maximizer and add the depth to the score if it was a win for the minimizer.

To use the above example, if the algorithm plays the bottom middle, it will win in three moves. At that point, the depth will be 2. So the score for that move will be 10 - 2 = 8. If the algorithm plays the bottom right, it wins right away with a depth of 0, so the score is 10. Since the algorithm will always choose the highest score for the maximizing player and the minimum score for the minimum player, the algorithm will now choose the quickest route to winning every time.

The maximum possible depth of tic-tac-toe is 9, since there are only 9 moves until a game is over. Therefore, choosing +10 and -10 as our winning values ensures that the maximizer score never goes negative and the minimizer score never goes positive. For more complicated games with deeper trees, dividing by the depth might be a better option to guarantee positive numbers stay positive and negative numbers stay negative.

Tips for Implementation

- Remember that minimax returns a score for each move. It does not return the actual move that was the best. You will want to have another function like

find-best-movethat will iterate through the available moves and call minimax on each move. If the score for the current move is higher than the previous move, update thebest-movevariable with that move. That way, after minimax has been called on each available move,find-best-movewill know the resulting best move to then send into your function that actually plays a move on to the board. - Make sure that every time minimax is called, it's changing what player it's simulating. This is often done with a boolean argument, but that isn't the only option.

- For the maximizer, we want to make sure that the initial score that it uses for comparison is so low that the first move will be the maximum score between the two. You could choose -1000, or -Infinity, anything unreachable. For the minimizer, we want the opposite, +1000 or +Infinity.

- The evaluation function that returns the score for wins or ties can do double duty for checking for a terminal game state to end your recursion. If it returns an enum, keyword, or string saying

:in-progressif there are no wins and no tie, then your recursive exit condition can be "if not :in-progress." - One flat array with nine elements is much easier to work with than multiple sub-arrays grouping things in rows and columns. The only time you need those sub-arrays is to check for if the game is won. Create a function that can take the one flat array and turn it into the eight different winning paths for when you need to evaluate the overall board state. Keep it flat the rest of the time.